Ioannis Tirkides*

Emmanuel Macron is still expected to win the presidential election in France, this Sunday April 24, but it will be a tight run according to polls, and French politics will not be the same after it. A close win will be more polarising and running the country will be harder than the previous time, in 2017, when Macron had won by landslide. Macron and Le Pen stand for different things, and the result of the election will matter also beyond France. It will matter for France’s position in the European Union. It will matter for the role of the European Union in Europe. And it will matter for Europe’s place and influence in global affairs. We discuss in this article what each candidate stands for, and what a win by each will mean for France and for the European Union. We argue that this is a historical moment and resonates with all the fundamental issues that will define politics and economics to the end of the decade.

Macron is a centrist-liberal candidate with a pro-reform and pro-European agenda. He sees France stronger only in a stronger European Union and a stronger France necessary for a stronger European Union. Marine Le Pen is the far-right candidate, not as extreme as Eric Zemmour, but a nationalist nonetheless and Eurosceptic. She does not argue for a French exit from the EU but that’s only in name as her opponents argue. As much as Macron will be about continuity, about a stronger France in a stronger Europe, Le Pen will be disruptive, prone to act unilaterally, and so will weaken the EU and reduce its influence in global affairs, as we discuss further below.

An election is a democratic and historical expression, and it is connected to the space and time it takes place. The issues and divisions that decide the election are long standing. They are the accumulation of past divisions and convergences, and the dilemmas ahead. On the domestic front, the French voters were moved by their economic conditions, inflation and the rising cost of living, the future of the health care system as a public good, and pensions, against a backdrop of an ageing population, high debt and zero interest rates. A declining population and a shrinking labour force will challenge to the welfare system. On the European front it is the eternal question of how much Europe do we want from the standpoint of the nation, and where do we want Europe in the global system. The latter is the old Gaullist and recurring theme of strategic autonomy.

No one questions the current economic predicament, and the challenges ahead, for France and for Europe. We may summarise in three words: growth, inclusivity, and climate. No one doubts that these challenges will consume us for the rest of the decade, in ways that will split and divide before they can unite. Take growth first. On average, ever since the global financial crisis of 2008-09, it has been lacklustre, and productivity has been slowing, sometimes even declining. Growth on the whole has been disappointing in advanced economies, despite the very accommodative monetary policies for so long. Now we are faced, not just by slower growth, but also by higher inflation, induced by pandemic and war, as well as the effects of domestic macroeconomic policies. Inflation is expected to be higher for longer and so there will be a trade-off between inflation and growth.

Growth has not only been slower but also less inclusive across nations and within nations. The gap between rich and poor countries has widened in the last 40 years or so. The richest in most societies are further ahead and intergenerational mobility has weakened. Inclusive growth has been made more difficult by the pandemic. Weakened and uneven income growth, high inequality, weak social mobility pose significant risks for society.

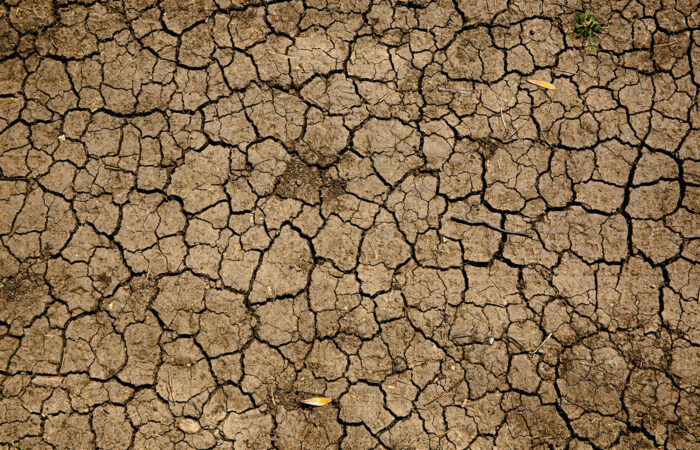

For climate change, the need for meaningful action is large and growing. The findings of the latest IPCC report are sobering. Even if the world were to follow through with current national climate commitments, temperatures will still rise by 2.2 degrees Celsius by the end of the century, a far cry from the threshold of 1.5 degrees.

How we respond to these challenges will be fundamental for the future of our societies. This is more important now than ever, because of the intensity of the issues and the interconnectedness of the global economy, which seems to be cracking, partly because of war and sanctions, and partly because of the rivalry and competition between the United States and China. Rightfully then, voters are split almost half and half, between opposing sides and more people are moving to the far right and the far left. It is seen in France now, as it was seen in the UK over Brexit, and in the United States in the last two presidential elections.

Macron stands foremost for self-reliance and more autonomy for France and for Europe. He stands for self-reliance in areas stretching from energy to manufacturing, research, and development, and also defence and security. He talks of massive state investments on the forefront of technological innovation. He argues for 100% French supply chains for electric vehicles, solar panels, and wind farms. Spending all this money will also add to France’s already large public debt at 115% of GDP in 2021, the fourth largest in Europe and may lead to some bumpy road in the end.

For Europe Macron wants more continent-wide programmes funded by borrowing at EU level, boosting industrial and energy independence. He wants greater scrutiny of companies from outside the European Union entering strategic sectors like telecommunications, energy, critical infrastructure and defense. He argues for strategic autonomy as the ability for Europe to shape world events. Back in January, before the war in Ukraine, Macron, talking before the European Parliament, at the beginning of France’s six-month presidency of the Council of the European Union, called for Europe to make ‘its unique and strong voice heard’ in the continent’s security. The question is, where do we want Europe to be in a world increasingly characterised by competition for influence between a rising China and the United States. Macron will want a stronger France in a stronger European Union, more autonomous and self-reliant and fully integrated with Nato.

Marine Le Pen in contrast, even if she stepped back from calling for a French exit from the European Union, she wants less of it. She campaigned to reduce France’s financial contributions to the European Union, and even to reintroduce border and customs controls. She calls for a referendum on a proposed law on ‘citizenship, identity and immigration’ to modify the constitution to allow a national priority for French citizens in employment and social security benefits. She wants to establish the ‘primacy of national law over European law’. This is ‘Frexit in all but name’ according to her opponents. A Le Pen victory therefore would be disruptive and would also increase financial uncertainty in the European Union, putting the future of the eurozone into question.

The stakes are high for France and for Europe, but the presidential election will not be the end of the electoral process in France. The elections for the National Assembly, the lower house of the French Parliament, will be held in June, and will determine the next prime minister, and the government’s ability to pass legislation. If different parties control the presidency and the national assembly, policy making could be disruptive. We will not know what France will emerge from this electoral process until then.

*Ioannis Tirkides is the Economic Research Manager at Bank of Cyprus and President of the Cyprus Economic Society. Views expressed are personal.