Maria Demertzis**

“There’s a fundamental truth of the twenty-first century within each of our own countries and as a global community,” President Joe Biden told the United Nations on 21 September. “Our own success is bound up with others succeeding as well.”

Biden’s actions, however, seem to take a different direction. The withdrawal from Afghanistan marked the end of the pursuit of one set of objectives, while the rekindling of an Anglo-Saxon alliance with the United Kingdom and Australia in AUKUS marked the pursuit of a different goal, that of containing China. Importantly, AUKUS also shows the limited patience the US has with the European Union when it comes to building ‘like-minded’ alliances to pursue its own strategic goals.

The EU, meanwhile, is not prepared to align its objectives just yet with the US when it comes to China. Europeans do not want to be in the middle of any emerging ‘cold war’ between the US and China. They do not believe that this war is about them and would not want to find themselves in the awkward position of having to choose between the two. The EU wishes to engage with China as a major trade and investment partner, so at the very least wishes to remain neutral. But it also wants to do so on its own terms, so can it afford to remain neutral?

The EU signed a comprehensive investment agreement with China at the end of last year. But this agreement has not been ratified and remains unimplemented. While the EU had very good reasons, namely the violation of human rights, to shelve the agreement, I wonder how it might have affected China’s perception of the EU’s willingness to engage and cooperate?

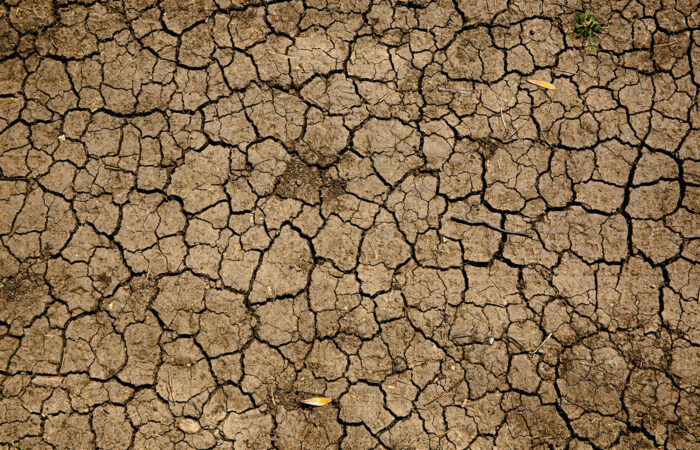

It is not difficult to imagine that with the US in open competition and the EU tacitly uncooperative, China is not going to volunteer to become, a good ‘global citizen’. Take climate for example.

It would be naïve for Europe and the US to expect China to cooperate on issues that relate to climate, while tolerating a Western alliance ‘attack’ on her economic strategy.

China has committed to becoming carbon neutral by 2060, ten years later than the EU and the US. Already this delay by a decade is a drain on the global carbon budget. Moreover, China’s emissions will continue to rise up to 2030, and there is significant doubt about whether she can meet either short- or long-term targets. If one considers that China’s annual per capita income ($9,700) is only a fraction of that of the EU ($36,000) and the US ($63,000), China has clear incentives to delay its climate adaptation.

Can we count on China’s willingness to cooperate on climate when its right to develop and grow disincentivizes her from doing so? At the very least, we should expect China to use climate as a lever to extract concessions on other issues.

But crucially what will happen to the EU’s and US’ climate goals if China chooses not to cooperate?

The answer to that question ought to help us understand the inconsistency between the global nature of the problems we face on the one hand, but forming only like-minded alliances, on the other.

The EU’s talk of ‘strategic autonomy’ shows its willingness, at least, to go it alone when it does not get what it wants. It remains to be seen how this will play out. Will the EU continue to pursue evasive neutrality, or will its words be backed by actions that guarantee its autonomy in the future?

In the US, it may be true that the ‘American first’ narrative is no longer present, but it has been replaced by one of ‘strategic retrenchment’: retreat and reconsider then regroup with all those whose interests and motives are aligned with those of the US. And as this is done from the position of military supremacy, the US wages, at the very least, a ‘cold’ war against China. One fears that it might end up being actual war.

All of this talk on strategic retrenchment and autonomy is the language of escalation, not of appeasement and collaboration. And yet, all agree, not least President Biden in his UN speech, that global commons require global solutions. It is inconsistent, if not outright harmful, to see global engagement dissolve to a race to the bottom.

* This piece was originally published in Kathimerini, a Greek newspaper, and also appeared as an opinion column on the Bruegel blog.

** Maria Demertzis is the Deputy Director at Bruegel, a Brussels based think-tank.