Charles Ellinas*

Climate summits are notorious for running overtime and into the weekend and COP29 is no exception. We have a deal of sorts. It was achieved early Sunday morning after acrimonious debates and a temporary walk-out from the summit by the small island nations.

COP29 was always going to be about money. The main priority at COP29 is agreeing on a new target to replace the current US$100bn a year that developed countries provide to developing countries to reduce emissions and adapt to disasters, that expires in 2025.

The key elements of the deal circulated on Sunday by the COP Presidency are:

- It calls on all parties to work together to enable the scaling up of financing to developing countries for climate action from all public and private sources to at least $1.3tn per year by 2025.

- The new climate finance goal (NCQG) is $300bn per year by 2035 that developed countries “will take the lead” to provide from a wide variety of sources, public and private

- It invites developing countries to make additional contributions, including through South-South cooperation, on a voluntary basis.

The latter refers to China, rich Arab countries and others to make appropriate voluntary contributions. In fact, China has already provided billions of dollars climate funds to developing countries.

COP29 was expected to be difficult even before it started. Poorer countries are very disappointed with this offer because they consider it to be too low and because they expected most of the $1.3tn to be from public sources and to be offered with no strings attached. But leaving COP29 without a finance deal could make the job at COP30 in Brazil next year that much harder.

Delegations will now assess the outcome, but concerns are growing about the likely non-cooperative position of the US on climate once Donald Trump becomes President in January.

Fossil fuels

One of the documents released by the COP29 presidency, as part of the final deal, is entitled “Taking forward the outcomes of the global stocktake.” It starts by reaffirming the outcomes of the first global stocktake at COP28 and it notes the work conducted under the UAE just transition work programme in 2024 and emphasizes the importance of its implementation.

What is known as the ‘UAE Consensus’, refers to “transitioning away from all fossil fuels in energy systems. This is the closest COP29 came to tackling fossil fuels. Though it is only an indirect reference, it nevertheless keeps the subject alive.

A deal on carbon markets

Another deal reached at COP29 on international carbon standards opened the way to set up UN-backed carbon markets, as set out in Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, that promise to generate billions of dollars for climate action.

There are two main mechanisms for such trading to take place. Under Article 6.2 countries can set up carbon trading arrangements bilaterally, and Article 6.4 outlines a system where trading would happen through an UN-backed carbon market, open also to business.

Under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, countries can transfer carbon credits earned from reducing their GHG (Greenhouse Gasses) emissions to help other countries meet their climate goals. This should help generate and inject billions of dollars into the fight against climate change.

Who decides on climate?

The UNFCCC insists that it is the only legitimate body to decide on climate and agree on the climate finance goal. But in reality, it is the G20 that can decide how that goal is reached. The G20 is where major economies make the decisions, and the UN is where all countries have a say.

But now we have another dimension. The election of Donald Trump to the US Presidency and his threat to pull the US out of the Paris Agreement, threatens to derail the outcome of COP29. It could prove to be “a major blow to global climate action.”

It has already introduced a great deal of uncertainty at a time when it is urgent to arrive at decisions on lowering emissions and tackling global warming.

Some doubts were expressed about the COP process and the slow pace of progress, calling for reform, but there is no consensus on alternatives.

Tackling emissions

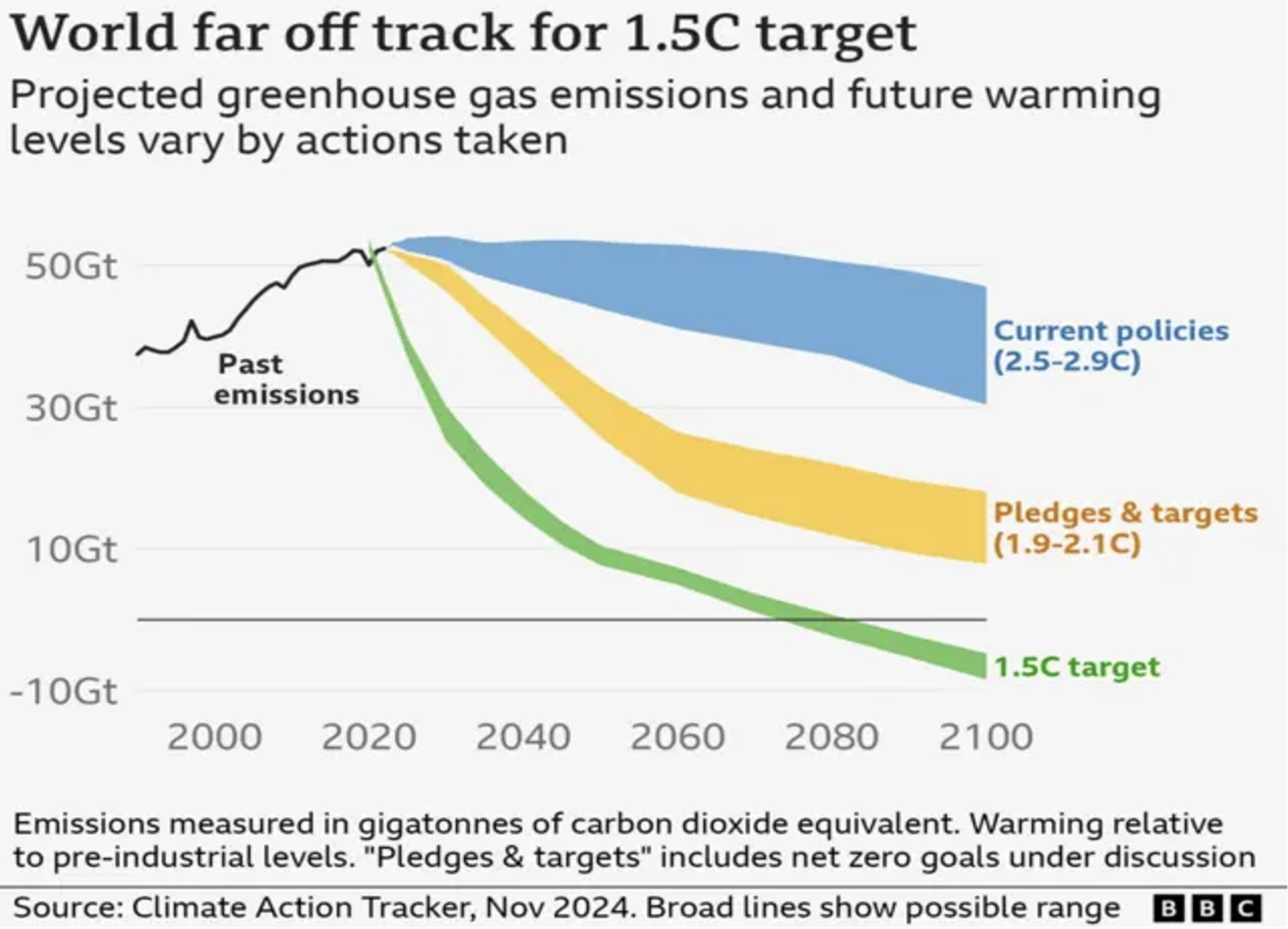

Little progress has been made in limiting emissions of greenhouse gases that are driving up temperatures. A recent UN report said global efforts to tackle climate change are seriously off track. New data shows that warming gases are accumulating in the atmosphere faster than at any time in human existence.

It is now more or less certain that 2024 will be the world’s warmest on record. Global average temperatures across the year are on track to end up more than 1.5C above pre-industrial levels, which would make 2024 the first calendar year to breach this “symbolic mark.”

This latest record helped focus minds at COP29 on the urgent need for action to limit any further warming.

A recent UN report warned that, without change, “the world is on track to reach 3C warming by the end of the century.” The UN says that limiting temperature rise to the 1.5C target is still “technically possible”, but only with huge cuts to emissions over the next decade, something that is verging on the impossible.

With Trump out is China coming in?

These are the initial indications. There are signs that China plans to take a more central role in the future. It is becoming more open about its plans and more participative in the COP process and may take a more active and cooperative role in future COPs.

For the first time, Chinese officials said at COP29 that the country has paid developing countries more than $24.5bn for climate action since 2016.

With demand for green technology likely to increase in developing countries because of the COP29 deal, China, being a major exporter of such technology, will have much to gain. Taking a more prominent role is in its interest and can only help.

Despite accusations that this was “one of the most chaotic COP meetings ever,” it has ended with a deal. It may not be quite what developing countries were hoping for, but it has, nevertheless, delivered substantially increased funds to tackle climate change. Viewed in the context of the current global political and economic environment, it is not a bad deal.

The world needs to find ways to reduce emissions in a constructive way and in a consistent approach. But it also needs to do that “while we are balancing the needs of people around the world to have affordable energy.”

*Charles Ellinas is Senior Fellow at the Global Energy Centre of the Atlantic Council.