Miranda Xafa*

Trump’s tariffs dominate discussions about the global economic order and the outlook for the global economy at the IMF’s Spring Meetings. Existing rules are being challenged, while new rules remain uncertain. Presenting its global economic outlook last Tuesday, the IMF predicted that Trump’s trade war would significantly increase the risk of a recession in America and push the global economy into a slowdown.

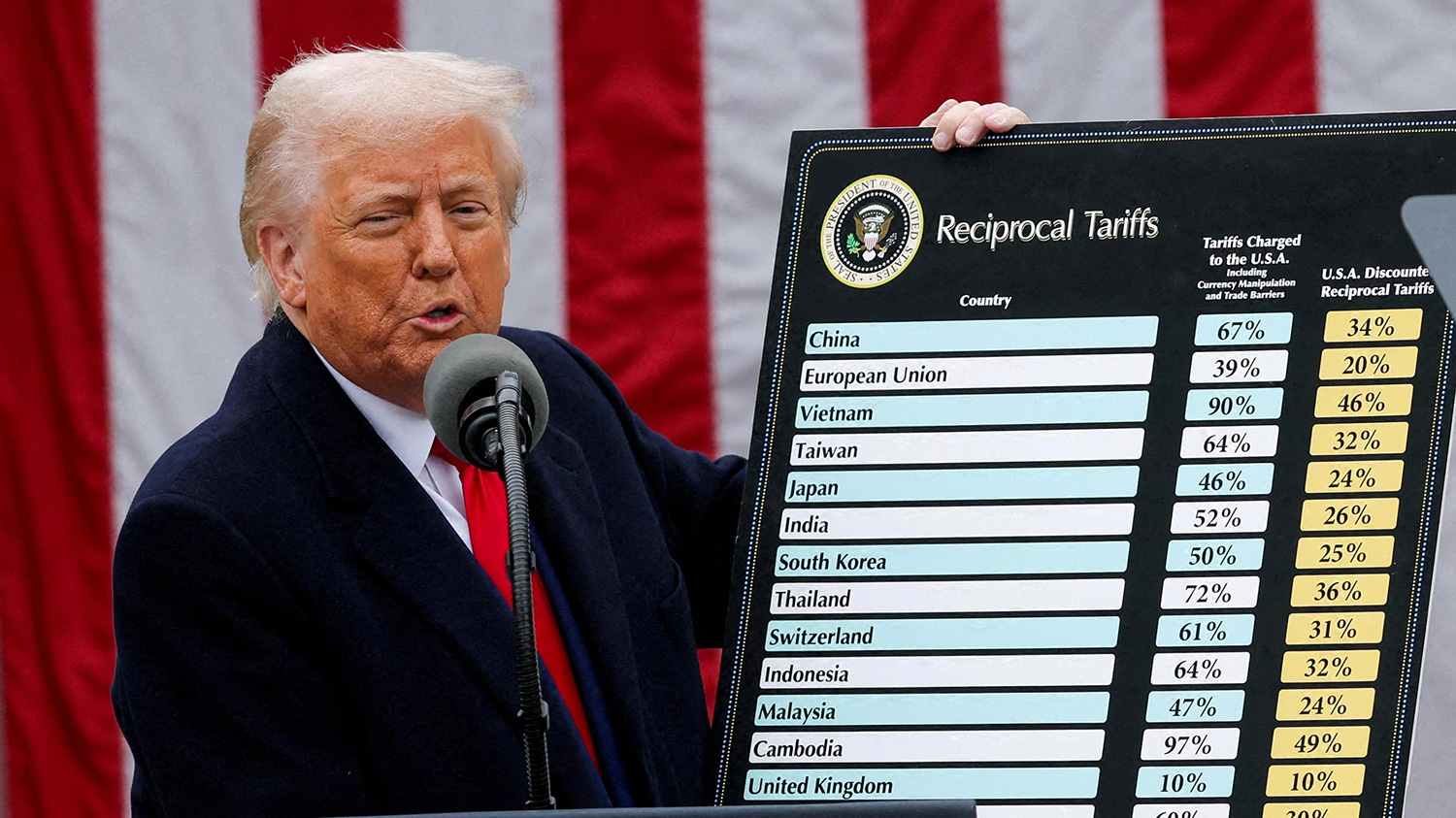

The tariff chaos that has roiled markets began on April 9 with the imposition of “reciprocal” tariffs ranging from 10% to 34% on America’s trading partners, in addition to the “universal” tariffs of 10% imposed on each country. Previously, the Trump administration had imposed tariffs of 25% on steel and aluminum imports, as well as 25% on Canada and Mexico, from which products covered by the USMCA trade agreement between the three countries were subsequently exempted. After the chaos caused in the global markets, Trump suspended the “reciprocal” tariffs for 90 days, except for the tariffs on China, which dared to retaliate. The dispute escalated with the imposition of 145% tariffs on China, but cell phones and other electronic devices were subsequently exempted from the tariffs, possibly under pressure from companies such as Apple, which are unable to produce in the US at competitive costs, and under the threat of large price increases in the US market.

Trump’s message is confusing. He’s calling for “reciprocal” trade, suggesting negotiations. On the other hand, he does not accept the proposals of his trading partners, even for zero tariffs on US products, and calls on companies to invest in America, assuring them that tariffs will not change. The only things that are clear are that he wants to reduce the trade deficit, raise revenue to finance the upcoming tax cuts, and bring manufacturing production back to the United States. How this would be achieved in an economy with just 4% unemployment remains a mystery. Moreover, the goals are contradictory: if he succeeds in repatriating manufacturing, he will not collect much revenue.

President Trump’s “reciprocal” tariffs are based on the mistaken belief that America’s large trade deficits reflect the country’s deindustrialization, as production shifts to countries with unfair trade practices. Fueled by bad accounting, this narrative now threatens to undermine both American prosperity and the liberal global order that sustains it. The mathematical formula used to determine the level of tariffs for each country was the ratio of the bilateral deficit to the country’s exports to America divided by two. If America has a bilateral deficit of 400 and imports 1,000 from the European Union, the tariff will be (400/1,000)/2=20%. This approach is based on the idea that America’s bilateral trade deficit with each country is the sum of all unfair trade practices and “cheating” by that country (intellectual property theft, state subsidies, etc.). Under time pressure, the Trump team has adopted an approach that is consistent with its political goals of “punishing those who cheated us”. This approach is not based on any economic logic.

- Bilateral deficits are based on each country’s comparative advantage and do not imply exploitation. The Nobel Prize-winning economist Robert Solow clarified this by saying: “I have a chronic deficit with my barber; I pay him every month, but he doesn’t buy anything from me.”

- Trade statistics record the full value of each product, not the value added. The full value of an iPhone assembled in China is recorded as an import from China, even though the design, software, project management, and other elements of its production are supported by high-paying jobs in the US, while many components are manufactured in third countries (e.g., screens in South Korea). This problem with bilateral trade statistics does not apply to the overall deficit, since everything must come from somewhere, so the overestimates and underestimates cancel each other out.

- The trade deficit is blamed for manufacturing job losses. But the share of manufacturing employment has been falling in all advanced economies in recent decades, even in economies with chronic trade surpluses such as China and Germany, due to automation.

- Tariffs on “strategic” sectors such as steel and aluminum hurt domestic industries that use these metals as raw materials (automobiles, construction). In the US, employment in the affected sectors far exceeds employment in the steel and aluminum sectors.

High tariffs can backfire. The 25% tariffs on steel and aluminum imports, intended to protect domestic production, are having the opposite effect, as price increases reduce demand from automakers. US automakers have also been hit by a 25% tariff on parts from Mexico, which benefits from cheap labor. The result is the layoff of hundreds of workers in these industries, with one of the largest steel producers, Cleveland-Cliffs, laying off 1,200 workers. Clearly no one wants to invest in America given the uncertainty.

Nobody knows where this trade war will lead. There are three factors that could cause Trump to back down: First, the markets, especially the bond market, where a massive selloff is pushing up yields and thus the cost of government borrowing. Second, congressional Republicans hoping to get re-elected in the 2026 midterms, when 84% of voters support free trade, which keeps prices low. Third, the Supreme Court, which will rule on the lawsuit filed by the governor of California against the administration’s tariff policy. Simple logic leads to the conclusion that the lawsuit is likely to succeed: To avoid submitting the tariffs to Congress for approval, Trump invoked the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), which gives the president expanded powers in the event of an extraordinary foreign threat to national security or the economy. The exemption of cell phones and other electronic devices from the tariffs imposed on China raises questions about whether invoking IEEPA is an abuse of power. Are shirts imported by the US from China a threat to national security or the economy, but electronic devices are not?

Trump has been characterized as a “transactional” leader. He makes deals that may yield short-term gains without regard to long-term goals related to credibility, respect for trading partners, or the rule of law. The tariffs and the way they were imposed undermine the global primacy of the US and the dollar. The damage to the US from Trump’s tariffs will be much greater than the losses in markets and the dollar so far. I will discuss this in a separate article.

*Miranda Xafa is member of the Academic Board of the Centre for Liberal Studies (KEFIM).