Maria Demertzis*

In its latest forecast published on 16 May, the European Commission expects inflation in the euro area to be 6.1% and growth 2.7% in 2022. The last forecasts published by the ECB on the 10 March, predicted inflation and growth at 5.1% and 3.7% respectively. These are big revisions for such a short time span, and they of course reflect the implications of the war in Ukraine.

The inflation and GDP growth outlook for the euro area gives the European Central Bank three issues to worry about.

The first headache that the ECB faces is that unlike in textbooks, inflation and output are now moving in opposite directions. This implies a trade-off, meaning ECB policy to tame inflation will necessarily make output deteriorate further. Many now talk about stagflation in the EU and euro area. There is some truth to this, as countries and the bloc will face weak growth and persistent inflation for some time.

However, it is also worth noting that the degree of stagflation, in order words the weakness of growth on the one hand and inflation pressures on the other, are nowhere near the stagflation of the early 80s. Back then, countries like France and Spain faced inflation rates of over 10%, even 20% in the case of Italy, as well as negative growth. The highest country inflation rate that we expect to see in the euro area this year is 6% and no country will grow by less than 1%. It is therefore a much lighter form of stagflation.

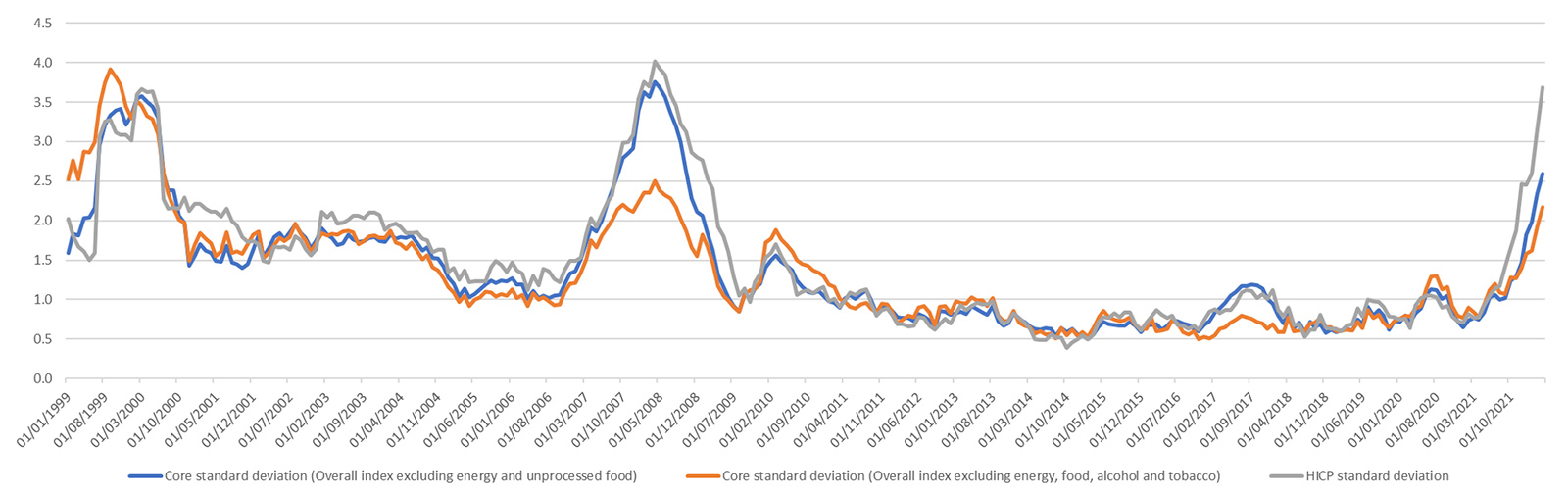

The second headache that the ECB faces has to do with inflation dispersion. Figure 1 plots the HICP inflation and two alternative definitions of core inflation, since the start of European Monetary Union in 1999. We observe three main peaks in the data. The first peak appears at the start of EMU and lasts about a year, the second peak at the start of the financial crisis lasts over 3 years, and the last is ongoing.

While the peaks are comparable in size, the reasons for them are different. Divergence during the financial crisis reflected the build-up of macroeconomic imbalances. However, the current differences in inflation reflect differences in geopolitical dependencies in terms of the energy mix and also in the energy intensity of production. On both occasions however, these divergences reflect structural differences in the economy and their (lack of) resilience to the running shock.

Figure 1: Inflation dispersion between countries in the euro area (%)

The third headache has to do again with country discrepancies but this time with the widening of country spreads that are already increasing. We know that country debts do not all reflect the same amount of risk. And in times of turbulence country spreads move to reflect this. However, this time is different in that it is monetary policy itself that is about to trigger this financial fragmentation.

Until now, and for as long as monetary policy had been expansionary, the objectives of price and financial stability were served simultaneously. However, now the ECB is about to come to the contractionary part of the monetary policy cycle, the objectives of price and financial stability push in opposite directions. As interest rates increase to tame inflation, the spreads between countries are going to increase, causing servicing costs to diverge between countries.

Given the non-negligeable weight of sovereign bonds in domestic banks’ balance sheets, heightened spreads can lead to financial instability. And in any case, diverging interest rates impairs the monetary transmission channel, which in turn threatens price stability and ultimately the single currency itself.

The ECB does not have suitable ready-made tools to apply directly. Given how important financial stability is for the euro area it must seek ways to at the very least neutralise the extent of the increase in spreads that itself triggers.

Even though inflation the in the euro area is smaller than that of the US, the three issues described make it a lot more difficult for the ECB to control inflation and preserve financial stability. Once again, the limits of EMU architecture become visible and will require a rethink.

*Maria Demertzis is the Deputy Director at Bruegel, a Brussels based think-tank. This piece was published as an opinion column on the Bruegel blog and re-posted on the blog of the Cyprus Economic Society