Ioannis Tirkides*

These are unprecedented times. We are simultaneously on the cusp of a technological revolution and the promise of unparalleled economic prospects, and on the brink of total war and the catastrophe it can bring. At no time since the end of the Cold War or its aftermath have conflicts been as intractable and potentially fatally escalatory as they are today. More worryingly, without a strategic reorientation by the major players – primarily the United States, but also Europe, Russia, and China – things could get much worse from here. The war in Ukraine is in its third year and the war in Gaza is in its seventh month. Meanwhile, there are other, even more dangerous flashpoints in Asia, where the rivalry between China and the United States is heating up. Meanwhile, Europe is caught in the middle, in the most unenviable position, and none of its leaders seems to grasp the moment, except perhaps the more nationalist and least welcome in Brussels. Nationalism recurs but is not the best guide to the future. And Cyprus is no stranger to it. In this article, we examine war and peace in a fragmenting world and consider Europe’s dire position in it.

You wouldn’t know it from the exuberance of the markets, but the world is on the brink. The Russians are winning in Ukraine and the Europeans are preparing to send troops. More war or defeat in Ukraine will be disastrous for Europe in particular, but also for the unity and cohesion of NATO. In the Middle East, we have just avoided, at least for now, what could have been a major conflagration following the exchange of drone and missile attacks between Israel and Iran. But this is not the end of their rivalry. The Israeli-Iranian conflict is not going away, and the danger of potentially drawing in the Americans and Europeans, who are allied with Israel, and Russia, which is allied with Iran, cannot be dismissed light-heartedly. There is no solution in sight in Gaza and Israel can’t rest in the comfort of Hamas being defeated, it hasn’t been defeated yet! At the same time there is trouble in the West Bank and more trouble with Hezbollah in Lebanon.

Nationalism is a growing, almost omnipresent force around the world. The liberal regimes that dominated Europe in the post-Cold War era are in trouble, and far-right parties are increasingly winning votes and seats in national and supranational parliaments. In the United States, the domestic political scene is far from reassuring. The political system is prosecuting Donald Trump. But whatever one thinks of him, and whatever his democratic credentials or lack of them, Trump is a leading candidate in November’s presidential election. Obstructing his candidacy or preventing his election is a recipe for social unrest before and after the election.

The big picture

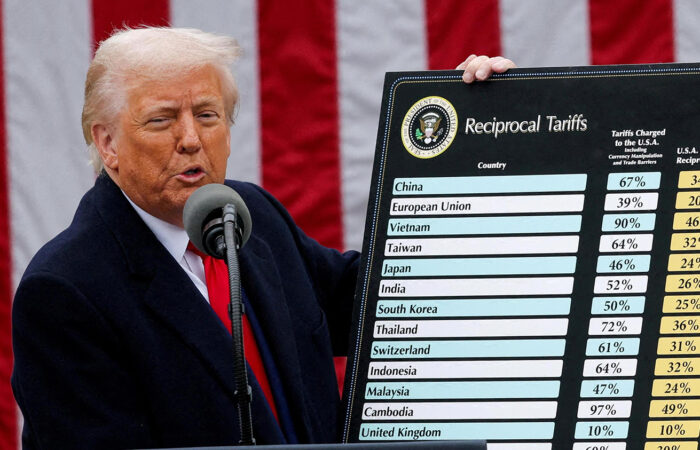

So, it is necessary to get the big picture right. The world is shifting from unipolarity to multipolarity, and the international economic and political order is fragmenting in its wake. The world is divided into two main opposing camps, the Group of the Seven richest countries led by the United States and an expanding BRICS led by China and Russia. No war has been declared between them, except by proxy, but their competition is intensifying at all levels – economic, commercial, and technological. There are many ways in which the world can get into trouble in the future. There is a de facto state of permanent hostilities and escalation is to be expected. This is the context in which we must try to understand the present and the future.

It is tempting to compare our current predicament with the old Cold War, but that would be misleading. There are important differences. Economically, China is a peer competitor of the United States in a way that the Soviet Union never was. Leaders then understood what was at stake and were realistic about national interests. That is not the case today. Worse, there are many competing regional powers in a context of potentially shifting alliances.

Existential wars

The wars in Ukraine and Gaza are intractable and prone to escalation. They are perceived by their actors as existential, and that is all that matters. For Russia, NATO’s expansion into Ukraine was unacceptable, just as missiles in Cuba were unacceptable to America in 1962. The American position that Ukraine will eventually join the Alliance, reiterated by Secretary Anthony Blinken, raises the stakes. If neither side can afford to lose the war for its own reasons, the war will not end and will be under constant threat of escalation.

Similarly, the war in Gaza is taking place because a two-state solution is unacceptable to Israel, perceived as an existential threat as it is. And a one-state solution in Greater Israel is an impossibility, given the underlying demographics of two roughly equal populations. The result is a perpetual state of war, with the ever-present risk of escalation. The dynamics of war in the Middle East have changed because of changes in the underlying technologies. The Houthis in Yemen, for example, with access to cheap but high-tech weapons, are able to close the Red Sea and Suez Canal to international trade, even against the United States. And the recent exchange of direct attacks between Israel and Iran has changed perceptions of the balance of power in the region, casting doubt on Israel’s ability to escalate to dominance, which has been its war doctrine since its founding in 1948.

Europe

How is Europe faring in all this? Badly, is the easy answer. But Europeans remain oblivious to the risks they have opened themselves up to. More importantly, the war in Ukraine, on European soil, is not going well for the West, but there is no talk of negotiations; instead, European governments are preparing for direct confrontation with Russia. Macron’s proposal to send troops to Ukraine caused an uproar in Washington and European capitals, but so did the idea of first, long-range missiles and then, F16 fighter jets. Each round of escalation adds a new layer of complexity that makes a solution even more difficult.

Contrary to popular belief, the war in Ukraine has not strengthened NATO, but weakened it, even as it has expanded it, with Finland and Sweden now its newest members. Divisions remain. Turkey has distanced itself from sanctions against Russia. Within the European Union, Hungary and Slovakia oppose further aid to Ukraine. Within the countries themselves, including France and Germany, public opinion is turning against the war. A defeat in Ukraine will further divide the alliance. Historically, whenever you suffer a serious defeat, everyone goes back and questions the causes and motives of the war, and if we go back to the causes of the war in Ukraine, it will not be a pretty picture for NATO and the West.

A helpless Europe faces an increasingly hostile Moscow, while the United States is increasingly preoccupied with its domestic affairs and its priorities in the Pacific. As reality turns upside down, Europe remains focused on yesterday’s priorities: net zero by 2050, defeating Russia, and further expansion into increasingly controversial parts of the world such as Ukraine and Georgia. But without affordable energy, European industry has no future. Without industry, Europe is irrelevant.

In conclusion

The world will never be the same again. The international system is fragmenting, trade flows are turning, and capital is migrating to friendlier shores in the Americas and parts of Asia. Europe is now the least competitive economic power and is almost entirely dependent on others for its defence, energy and even some of its food. Being dependent on others for the most vital parts of organised society, as Europe is, is not an enviable position. It is a strategic failure, especially in an era of geopolitical dominance. Europeans, we have been too complacent, too self-congratulatory, too micro-minded, perhaps over-managed and certainly under-led.

*Ioannis Tirkides is the Economics Research Manager at Bank of Cyprus and President of the Cyprus Economic Society. Views expressed are personal.