In a previous article published last week, we examined the political landscape in Cyprus since 2011 against a backdrop of rising right-populism in advanced liberal democracies over the past couple of decades and more. Populism as we have known it in advanced liberal democracies is not a homogeneous phenomenon, but it is not a transient one either. It is rooted in four main factors: the distrust of politicians, the cultural threat primarily from immigration, the economic deprivation from successive economic crises, and the weakening of party loyalties. These factors taken together, which are not stranger to the Cypriot reality, give politics a different prospect altogether, and it may be telling of more political volatility for longer. In Cyprus we have been witnessing the fragmentation of the political landscape, and the accompanying rise in nationalism and populism since the 2011 parliamentary elections. Now, ahead of the presidential elections in February, we are witnessing a reflection of the same fragmentation in a diversity of alliances not always with clear associations, or commonality of objectives. This happens against a background of party division internally, a rise in external threats in relation to Turkey, and of withering prospects for a negotiated solution of the Cyprus problem. In this second part we ask who is voting for who, in the coming presidential elections of February 2023, and what delineations can be drawn from this.

We conclude that the dividing line that distinguishes the main candidates, is the Cyprus problem and the failure to agree what a viable solution should look like. Sadly, the structure of the campaign does not properly reflect this dichotomy, between the pro-solutionists and what we may call hardliners on the other side, subordinating instead an existential issue to parity with a multiplicity of important but lesser issues. The election is a prelude to more internal division, that will only aid Turkey’s renewed assertiveness. Failure to return to the negotiations quickly, will only exacerbate tensions.

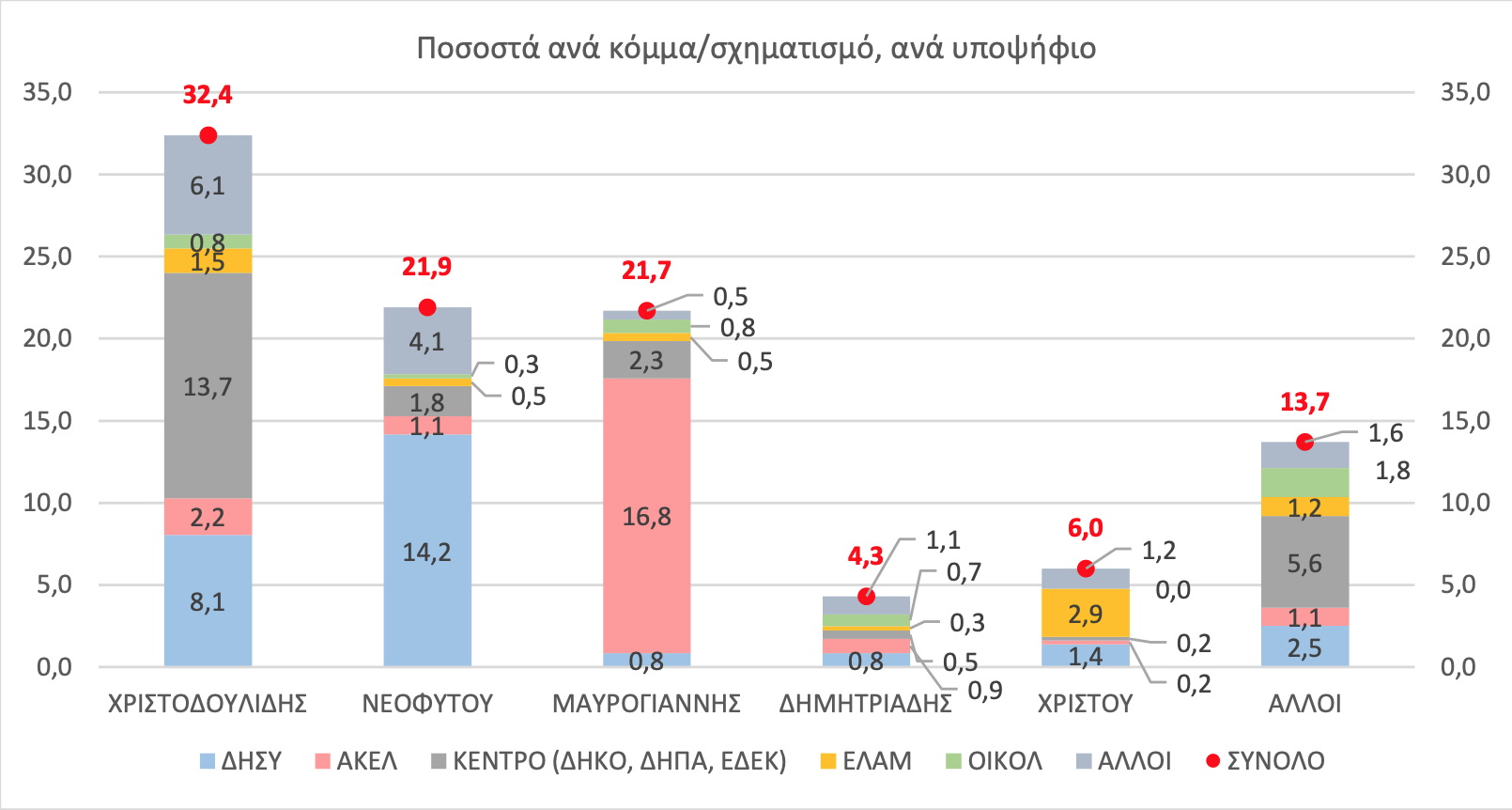

Leading in the polls is the presidential candidate Nicos Christodoulides, followed by DISY candidate Averof Neofytou, and AKEL-backed Andreas Mavroyiannis. ELAM candidate Christos Christou and independent Achilleas Demetriades make a noticeable presence. Divisions and broken loyalties are observed across all political parties, which makes the election more unpredictable than we may think.

Nicos Christodoulides is a former career diplomat and has been member of the government of president Anastasiades for nine years as spokesman, head of the president’s diplomatic office, and lastly foreign minister from 2018 to 2021. Nicos Christodoulides was member of the ruling party DISY and declared his candidacy for the presidential elections while remaining member of the party. Mr Christodoulides formally secured the support of DIKO, DIPA, EDEK, and the Solidarity party. He polls 32.4% of which only 42% or 13.7 points comes from the centre parties that formally support him. Another 25% or 8 points come from DISY; 7% or 2.2 points from AKEL; 5% or 1.5 points from ELAM; 3% or 0.8 points from the GREENS; and 18% or 6 points from all the rest. Interestingly, about one third of this support or more than 10 points, comes from DISY and AKEL together. Losing this support would significantly reduce his chances for making it to the second round.

The support from DISY is particularly large, suggesting a significant rift within the party ranks, which wouldn’t be possible without significant support from the upper echelons. This is the second time in the history of DISY when the party candidacy faces division from within. The first time was in the presidential elections of 2003, when the then incumbent president Glafcos Clerides stood for re-election asking for sixteen months to complete negotiations for a solution of the Cyprus problem and put it to a national referendum. Other candidates refused to unite behind him to try and reach a settlement. Clerides’ campaign was hurt by the decision of his close aide and attorney general Alecos Markides, also hailing from DISY, to stand in the election as an independent. His candidacy split the DISY vote and Tasos Papadopoulos, leader of the Democratic Party, supported by left-wing AKEL, was elected from the first round.

DISY candidate Averof Neophytou and AKEL backed Andreas Mavroyiannis, poll respectively 21.9% and 21.7%, and derive their support mostly from the respective parties. Averof Neophytou derives 65% of his polling from DISY and Andreas Mavroyiannis derives 77% of his polling from AKEL. Their penetration to the centrist parties backing Christodoulides, while not insignificant, is limited. Averof Neophytou derives 8% of his vote or 1.8 points from these parties, and Andreas Mavroyiannis derives respectively 11% or 2.3 points of his. All numbers except the percentages are illustrated in the accompanying chart.

Nicos Christodoulides is not a populist revolt against the corruption of the establishment. Himself denies the government he was member of, for nine years, was corrupt. And if president Anastasiades as presumed in the press at least, is behind his candidacy, this is a continuation of that regime and not a change of it, that almost guarantees the outgoing president a role in the affairs of his party and in the country presumably, after the election.

The question to ask is, what essentially drives the coming election? Is it economics, culture, or the aging Cyprus problem? The economic storyline that incumbent candidates put forth for performance and credibility is exaggerated. Economic policy can make a lot of good and a lot of harm at times, but the economy operates largely independently, and sometimes despite policies. Ever since the 2008-09 global financial crisis, most economies in the advanced world have been benefiting from substantial fiscal and monetary stimulus, ‘magic money’ and debt accumulation. The Cyprus economy over the past ten years has been greatly aided by unprecedented amounts of support. This includes the bail-in of depositors, Europe’s bail-out programme, the fiscal expense for the resolution of the Cyprus Cooperative Bank, the substantial inflows from the citizenship by investment programmes, and even the fiscal support in the Covid-19 pandemic. Adding all of these together the sum is in the tens of billions and certainly exceeding the size of one annual GDP.

Political culture is about corruption, identity, and sovereignty issues. Oddly enough, corruption doesn’t rank high in the campaign as evidenced by the fact that two of the front runners in this election, Mr Neophytou and Mr Christodoulides, hail from the previous government and from the same party.

Matters of identity relate partly at least to the problem of illegal immigrants which in an important way links up with the Cyprus problem. Thus, the old and ageing Cyprus problem is what divides the competing candidates foremost.

There is a clear demarcation line here, between two opposing camps. The rejectionists or hardliners, who rally behind Nicos Christodoulides, and the pro-solutionists that many other candidates purport to be.

The rejectionist camp and its candidate reject the Guterres framework, they stress national identity and propose ‘new’ methodologies, principally the deeper involvement of the EU in the negotiations. President Anastasiades even campaigned for this idea, or for its originator, in two of his last few trips one to France, anther to Germany, where he pressed the point to President Emmanuel Macron and Chancellor Olaf Scholtz. But how credible is this? Ever-since 2004, the EU has always been part of the negotiations because all parties accepted it. It is not a new idea nor is it a constructive one. It cannot happen without Turkey’s approval or without sidestepping the United Nations, which would be a very dangerous development if it were to happen.

The pro-solutionist camp is more fragmented, and its messages are not very clear. Mr Averof, even if belatedly, and Mr Demetriades from the start, clearly support the Guterres framework. Mr Mavroyiannis is not certain if there is one.

If the pro-solutionist camp is as fragmented, lacking commonality on such basics, they will not be able to go very far in the second round. If this election is primarily about the Cyprus problem as we thin k it is, and about salvaging the prospect, the pro-solutionist campaign needs to change its tune and focus urgently. For certain, the Cyprus problem will not be around as we know it today, in the next presidential election, if we fail to restore the negotiations from where they were last. It will be a pity if we don’t try to change that predicament.

*Ioannis Tirkides is the Economics Research Manager at Bank of Cyprus and President of the Cyprus Economic Society. Views expressed are personal.